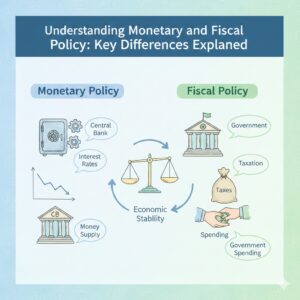

In the complex machinery of a modern economy, stability is rarely the default state. Markets breathe through cycles of expansion and contraction, often driven by shifts in consumer confidence, technological disruptions, or global events. To navigate these turbulent waters, governments employ two primary levers: monetary policy and fiscal policy.

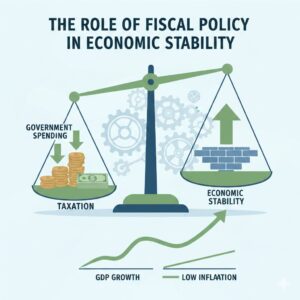

While monetary policy deals with interest rates and the money supply, fiscal policy is the government’s direct hand on the wheel. By adjusting spending levels and tax rates, a nation can influence aggregate demand, manage inflation, and foster sustainable growth.

1. Defining Fiscal Policy: The Basics

Fiscal policy refers to the use of government revenue collection (taxes) and expenditure (spending) to influence a country’s economy. The primary goal is to maintain a “Goldilocks” state—an economy that is neither too hot (leading to runaway inflation) nor too cold (leading to recession and unemployment).

The Two Main Instruments:

- Government Spending: Investment in infrastructure, education, defense, and social safety nets. This injects money directly into the economy.

- Taxation: Income, corporate, and sales taxes determine how much disposable income households and businesses have.

2. Expansionary vs. Contractionary Policy

Governments must be adaptive. Depending on the current economic climate, they will choose one of two paths:

Expansionary Fiscal Policy

When the economy is sluggish or in a recession, the government seeks to “prime the pump.” It does this by:

- Lowering taxes to increase consumer spending.

- Increasing spending on public projects to create jobs.

The goal here is to shift the aggregate demand curve to the right. This is often associated with Keynesian Economics, which suggests that during a downturn, private sector inactivity must be compensated for by public sector action.

Contractionary Fiscal Policy

When an economy grows too quickly, it risks “overheating,” which leads to high inflation. To cool things down, the government may:

- Raise taxes to reduce the money available for consumption.

- Cut spending to lower the overall demand for goods and services.

While politically unpopular, this is essential for maintaining the long-term purchasing power of the currency.

3. The Multiplier Effect: Turning $1 into $3

One of the most powerful concepts in fiscal policy is the fiscal multiplier. When the government spends money on, say, a new bridge, it doesn’t just help the construction company.

The workers on that bridge spend their wages at local grocery stores; the grocery store owner uses that profit to buy a new car; the car salesman spends his commission elsewhere. In theory, an initial injection of government spending can lead to a total increase in National Income that is greater than the original amount spent.

Where MPC is the Marginal Propensity to Consume (the percentage of additional income a consumer spends rather than saves).

4. Automatic Stabilizers: The Silent Guards

Not all fiscal policy requires a new law to be passed. Automatic stabilizers are built-in features of the budget that act instantly to dampen economic fluctuations.

- Progressive Income Taxes: As people earn more during a boom, they naturally move into higher tax brackets, which slows down overheating without any new legislation.

- Unemployment Insurance: During a recession, more people claim benefits. This automatically increases government spending, providing a safety net that keeps demand from bottoming out.

5. Challenges and Limitations

If fiscal policy were easy, recessions wouldn’t exist. However, several “lags” and hurdles make it difficult to execute perfectly:

The Timing Lag

- Recognition Lag: The time it takes to realize a recession is happening.

- Implementation Lag: The time it takes for Congress or Parliament to debate and pass a spending bill.

- Impact Lag: The time it takes for the spent money to actually filter through the economy.

The “Crowding Out” Effect

If a government borrows too much money to fund its spending, it may drive up interest rates. Higher interest rates make it more expensive for private businesses to borrow and invest, effectively “crowding out” the private sector and neutralizing the benefits of the initial government spending.

Public Debt Concerns

Persistent use of expansionary policy leads to budget deficits. While debt is a tool, an unsustainable debt-to-GDP ratio can lead to a loss of investor confidence and future austerity measures that hinder long-term growth.

6. Fiscal Policy in the 21st Century

Recent history, specifically the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 global pandemic, saw a massive resurgence in fiscal intervention. Governments worldwide moved away from “austerity” and toward “stimulus,” proving that in times of extreme crisis, the state is often the only entity capable of preventing a total economic collapse.

Today, the focus is shifting toward “Green Fiscal Policy,” where tax incentives and government spending are used not just for stability, but to transition economies toward renewable energy—a marriage of economic stability and environmental sustainability.

Conclusion

Fiscal policy is the bridge between theoretical economics and the lived reality of citizens. When handled with precision, it provides the infrastructure, safety nets, and stability necessary for a flourishing society. However, it requires a delicate balance; too much intervention risks debt and inflation, while too little leaves the most vulnerable exposed to the whims of the market.

As we look toward the future, the role of fiscal policy remains clear: it is the essential toolkit for building a resilient, equitable, and stable global economy.